or Download presentation as pdf

Why do we sing?

Music has been a part of the lives of human beings throughout history and in cultures all over the world. It has been used by men to express things that defy simple definition and to transcend more common methods of communication. As infants, lullabies sooth us to sleep. As children, our play is alive with simple story songs and rhymes. As adults we sing about our history and legends; our loves and dreams. Music and rhythm wind around and through our lives adding depth and enriching our experiences. God put this desire and ability in us and commands us to use it when we worship Him.

A Brief History of Church Music

Note: A timeline on the history of church music might be helpful for this section.

We have a rich history of singing to and about God in worship. From the recitation of the simplest metrical Psalm to the most sublime artistic offerings of high church music, we are called by God to try to express the inexpressible to the unapproachable Creator of everything through our Saviour Jesus Christ. The Bible tells us that true worship happens in spirit and in truth, and when we sing our best before God we are not judged by our abilities but rather by our obedience to His commandment to worship Him in song. Here is what John Wesley had to say about singing to God.

"Above all, sing spiritually. Have an eye to God in every word you sing. Aim at pleasing him more than yourself, or any other creature. In order to do this, attend strictly to the sense of what you sing, and see that your heart is not carried away with the sound, but offered to God continually; so shall your singing be such as the Lord will approve here, and reward you when he cometh in the clouds of heaven."

John Wesley in Select Hymns, 1761

The purpose of our worship is not to fulfill something God needs, but rather it is something He knows, as our maker, that we need to do. Our worship draws us to Him and prepares us for the service He has called us to perform in the world outside of His sanctuary. His command to make music is much the same; it is not something He needs to hear as much as it is something we need to do. It touches us at a deeper level than words alone and gives a language to the emotions we feel in response to God's grace in Jesus Christ.

Music in the Bible

The Bible describes music in many forms including singing, playing musical instruments and even in the non-human music of the angelic chorus singing praise to God in Heaven. As for singing specifically, the various forms of the verb "sing" appear 100 times in the Bible. God created us to sing His praises and tells us in scripture to make singing a part of our worship.

The Psalms contain many references to praising God in song. The Levities in Old Testament worship used instrumental music and singing as a priestly function accompanying sacrifice. Here is one of the many musical Psalms.

4Make a joyful noise to the LORD, all the earth; break forth into joyous song and sing praises. 5Sing praises to the LORD with the lyre, with the lyre and the sound of melody. 6With trumpets and the sound of the horn make a joyful noise before the King, the LORD.

Psalms 98:4-6 (NRSV)

Paul's letters to the early Christian churches also directed the use of music as part of living lives for Christ. He even names three specific types of songs we are to use.

18b...Be filled with the Spirit, 19as you sing psalms and hymns and spiritual songs among yourselves, singing and making melody to the Lord in your hearts, 20giving thanks to God the Father at all times and for everything in the name of our Lord Jesus Christ.

Ephesians 5:18-20 (NRSV)

16Let the word of Christ dwell in you richly; teach and admonish one another in all wisdom; and with gratitude in your hearts sing psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs to God. 17And whatever you do, in word or deed, do everything in the name of the Lord Jesus, giving thanks to God the Father through him.

Colossians 3:16-17 (NRSV)

Thomas Aquinas, in the introduction to his commentary on the Psalms, defined the Christian hymn thusly "A hymn is the praise of God with song; a song is the exultation of the mind dwelling on eternal things, bursting forth in the voice." We were created to sing God's praises and God Himself inspires the words and musical forms we use in our worship services today. In our Psalms we praise God's characteristics and benefits. In our Hymns we express our belief in our salvation and our response to His Son's love for us. In our Spiritual Songs we sing about how the Holy Spirit is with us and changes our lives. All of these should be part of our worship.

Music in the Early Church

Historians believe that the earliest Christian music followed the forms laid out in the Jewish Psalms. This is the subject to some debate because until the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed in 70 A.D., only the Levities sang to God and only during sacrifices in the Temple. It wasn't until after the Temple was destroyed that Jewish Synagogic worship was expanded from its role of simple reading and analysis of the words of the Torah and the prophets to include more of the elements of Temple worship, including singing and musical instruments.

In many ways, the forms of Jewish worship were changing at the same time that early Christians were exploring how to approach the worship of God. There is very little documentation about how the earliest Christians worshipped. This was partly due to the systematic persecution of Christians which caused them to worship in homes and other hidden places. Once Roman Emperor Constantine I converted to Christianity in the the 4th century, the church began to keep records that give insight to the practices of that and later times.

The predominant form of music in the early church was a form of liturgical chant originally developed in the Byzantine Empire. It is a compositional form drawn from the classical age, Jewish worship music, and was influenced by the monophonic vocal music that evolved in the early Christian cities of Alexandria, Antioch and Ephesus. A system of writing down reminders of chant melodies was probably devised by monks around 800 to aid in unifying the church service throughout the Frankish empire. During this time, the plainsong chants from this period were referred to as Gregorian Chants in honor of Pope Gregory I, even though he served over two hundred years earlier.

One of the oldest examples of a chanted hymn not found in scripture is called Phos Hilaron and was originally written in Greek in the 4th century. The hymn is featured in the vespers of the Byzantine liturgy used by the Orthodox and Eastern-rite Catholic traditions, as well as being included in some modern liturgies as 'O Gladsome Light'.

O Gladsome Light of the holy glory of the Immortal Father, heavenly, holy, blessed Jesus Christ. Now we have come to the setting of the sun and behold the light of evening. We praise God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. For it is right at all times to worship Thee with voices of praise, O Son of God and Giver of Life, therefore all the world glorifies Thee.

'O Gladsome Light' or Phos Hilaron (Φῶς Ἱλαρόν)

The first polyphonic music was a variation of Gregorian chant called organum. In its earliest stages around 900 A.D., organum involved two musical voices: a Gregorian chant melody, and the same melody transposed by a consonant interval, usually a perfect fifth or fourth. In these cases often the composition began and ended on a unison, maintaining the transposition only between the start and finish. Organum was originally improvised; while one singer performed a notated melody (the vox principalis), another singer, singing by ear, provided the unnotated second melody (the vox organalis). Over time, composers began to write added parts that were not just simple transpositions, and thus true polyphony was born.

Polyphony initially offended the medieval ears of the church because it allowed secular music to merge with the sacred. In their minds it removed the solemn quality of church music. Harmony seemed to make worship music frivolous, impious, and lascivious, as well as an obstruction to the audibility of the words. Some instruments and certain modes (musical term similar to modern key signatures), were actually forbidden in the church because of their association with secular music and pagan rites. Dissonant notes gave a creepy feeling that was labeled as evil, fueling their argument against polyphony as being the devil’s music. It wasn't until 1364, during the pontificate of Pope Urban V, that composer and priest Guillaume de Machaut composed the first polyphonic setting of the mass called La Messe de Notre Dame. This was the first time that the Church officially sanctioned polyphony in sacred music.

Music in the Roman Catholic Church

The supremacy of the the Church in Rome over the other Christian churches of that time was largely due to legacy of the strength of the Roman Empire. In 1054 A.D. the conflict between Rome and other churches over the issues of supremacy and theology resulted in the mutual excommunications by the Pope in Rome and the Patriarch in Constantinople. This created what eventually became the Roman Catholic church. The other churches of that time still exist today as the Eastern Orthodox church.

The music and liturgy of the Roman Catholic church was rooted in Latin and it was used in all church writings and worship services. We still see latin influences in music today. In contrast, many Eastern Orthodox churches still use or are influenced by greek and other cyrillic languages which were in common use when those churches were founded.

The order and components of worship services began to become even more formal and soon the participation by congregations of the Roman Catholic Christian began to include more than just singing praises to God. Their part in worship services included intoning liturgical responses or refrains, acclamation, the Doxologies, the Alleluias, the Hosannas, the Trisagion (a form of Holy, Holy, holy or the Sanctus), and the Kyrie Eleison (God have mercy). The music became more ornate and difficult to sing, so the church began to hire and train professional musicians to lift voices in song to God. Many of these formal styles of worship music are still performed today as the Mass, the Requiem, the Te Deum and the Magnificat.

It was during this period that the pipe organ, invented sometime before the 6th century, installed in churches began to resemble modern pipe organs with familiar weighted and balanced keys. Church music in this period began to establish musical styles and notation that can still be used today. The kinds of polyphonic music, instrumentation and musical notation developed supported the sweeping changes brought by the reformation and the renaissance.

Music in the Reformed Church

During the renaissance in the 15th and 16th centuries, leaders of the Roman Catholic church began to criticize many aspects of their church practices. Martin Luther posted 95 specific issues he had with the Roman Catholic church to the front door of the church in Wittenberg, Germany. That action is regarded as the beginning of the Protestant Reformation and marked the start of changing how Protestant Christians worship.

One of the issues that early reformers had with worship was the extravagant and ornate form that services and worship music had evolved into. The early Reformers wanted congregational participation in singing rather than the elaborate choral pieces that the congregation only listened to. Luther wrote his own hymns set to popular tunes while Calvin wanted only Psalms. Calvin actually translated a few Psalms into metrical form (in French) and later commissioned better poets to do the translation for him. He specified that they had to be set to very simple tunes - generally only two values - whole notes and half notes or half notes and quarter notes - no syncopation and no harmony.

Some modern reformed denominations still only use words that are a direct translation from the Bible and only use instruments to lead the congregations voices in song. During the late 19th and 20th centuries, many new styles of music were brought into the church. Some of these styles were a continuation of the modern forms of classical music, but other, more relaxed styles of popular music were introduced as well.

One of the highlights of Protestant worship is the emphasis on congregational singing. This returned to the congregation the responsibility to sing God's praises as we are instructed. Some in the congregation may lead songs individually or in a choir, but it is the hymn book found in the back of our pews that is one of the most obvious differences between Protestant and Catholic worship.

Modern Presbyterian Worship

Modern Presbyterian churches have denominational guidelines, but do not have strict liturgical rules regarding the forms of music used during worship. Some churches still use the traditional hymns and anthems of the previous century. Some churches have stopped using the choirs and organs of the past to embrace music that requires modern electronic instruments and simpler song forms. Regardless of the styles, music remains a core part of modern Presbyterian worship.

The Book Of Order

The Book of Order contains the following direction for the use of music in worship services.

(2) The Reformed heritage has called upon people to bring to worship material offerings which in their simplicity of form and function direct attention to what God has done and to the claim that God makes upon human life. The people of God have responded through creative expressions in architecture, furnishings, appointments, vestments, music, drama, language, and movement. When these artistic creations awaken us to God’s presence, they are appropriate for worship. When they call attention to themselves, or are present for their beauty as an end in itself, they are idolatrous. Artistic expressions should evoke, edify, enhance, and expand worshipers’ consciousness of the reality and grace of God.

Book Of Order, Directory for Worship, W-1.3034 - Artistic Expressions

Song is a response which engages the whole self in prayer. Song unites the faithful in common prayer wherever they gather for worship whether in church, home, or other special place. The covenant people have always used the gift of song to offer prayer. Psalms were created to be sung by the faithful as their response to God. Though they may be read responsively or in unison, their full power comes to expression when they are sung. In addition to psalms the Church in the New Testament sang hymns and spiritual songs. Through the ages and from varied cultures, the church has developed additional musical forms for congregational prayer. Congregations are encouraged to use these diverse musical forms for prayer as well as those which arise out of the musical life of their own cultures.

Book Of Order, Directory for Worship, W-2.1003 - Music as Prayer: Congregational Song

To lead the congregation in the singing of prayer is a primary role of the choir and other musicians. They also may pray on behalf of the congregation with introits, responses, and other musical forms. Instrumental music may be a form of prayer since words are not essential to prayer. In worship, music is not to be for entertainment or artistic display. Care should be taken that it not be used merely as a cover for silence. Music as prayer is to be a worthy offering to God on behalf of the people. (See also W-2.2008; W-3.3101)

Book Of Order, Directory for Worship, W-2.1004 Music as Prayer: Choir and Instrumental Music

The Word is also proclaimed through song in anthems and solos based on scriptural texts, in cantatas and oratorios which tell the biblical story, in psalms and canticles, and in hymns, spirituals, and spiritual songs which present the truth of the biblical faith. Song in worship may also express the response of the people to the Word read, sung, enacted, or proclaimed. Drama and dance, poetry and pageant, indeed, most other human art forms are also expressions through which the people of God have proclaimed and responded to the Word. Those entrusted with the proclamation of the Word through art forms should exercise care that the gospel is faithfully presented in ways through which the people of God may receive and respond.

Book Of Order, Directory for Worship, W-2.2008 - Other Forms of Proclamation

(3) Music may serve as presentation and interpretation of Scripture, as response to the gospel, and as prayer, through psalms and canticles, hymns and anthems, spirituals and spiritual songs. (W-2.1003 2013.1004; W-2.2008)

Book Of Order, Directory for Worship, W-3.3101 - What Is Included: Music

These statements are worthy of our attention and consideration as we approach God in song as a congregation in Christ's church. They provide us guidelines to use to evaluate our decisions regarding the choices of how to use music in Presbyterian worship.

The Theater of Worship

Another valuable concept to help us understand our role in worship was written by the 19th century Danish philosopher and theologian Sören Kierkegaard. He described what has come to be called the "theater of worship" to instruct us on how we should consider our role in the worship of God. Here are his words.

In order that no irregularity may be admitted or no double-mindedness left unmentioned, let me then at this point, where the demand is being made for a person’s own activity, briefly illustrate the relation between the speaker and the listener in a devotional address. Let me in order once again to take up arms against double-mindedness, make this illustration by borrowing a picture from worldly art. And do not let the two senses in which this may be taken disturb you or give you grounds for accusing the address of impropriety. For if you have dared to attend an exhibition of worldly art, then by doing this, you yourself must have come to understand what is meant by spiritual. Therefore you must have considered the spiritual with the worldly art even though it was the means of your first distinct recognition of the difference between the two. If you did not, discord and double-mindedness are in your own heart, so that you live for periods of time on the worldly plane with only an occasional thought of the spiritual. It is so on the stage, as you know well enough, that someone sits and prompts by whispers; he is the inconspicuous one, he is, and wishes to be overlooked. But then there is another, he strides out prominently, he draws every eye to himself. For that reason he has been given his name, that is: actor. He impersonates a distinct individual. In the skillful sense of this illusory art, each word becomes true when embodied in him, true through him -- and yet he is told what he shall say by the hidden one that sits and whispers. No one is so foolish as to regard the prompter as more important than the actor.

Now forget this light talk about art. Alas, in regard to things spiritual, the foolishness of many is this, that they in the secular sense look upon the speaker as an actor, and the listeners as theatergoers who are to pass judgment upon the artist. But the speaker is not the actor -- not in the remotest sense. No, the speaker is the prompter. There are no mere theatergoers present, for each listener will be looking into his own heart. The stage is eternity, and the listener, if he is the true listener (and if he is not, he is at fault) stands before God during the talk. The prompter whispers to the actor what he is to say, but the actor’s repetition of it is the main concern -- is the solemn charm of the art. The speaker whispers the word to the listeners. But the main concern is earnestness: that the listeners by themselves, with themselves, and to themselves, in the silence before God, may speak with the help of this address.

The address is not given for the speaker’s sake, in order that men may praise or blame him. The listener’s repetition of it is what is aimed at. If the speaker has the responsibility for what he whispers, then the listener has an equally great responsibility not to fall short in his task. In the theater, the play is staged before an audience who are called theatergoers; but at the devotional address, God himself is present. In the most earnest sense, God is the critical theatergoer, who looks on to see how the lines are spoken and how they are listened to: hence here the customary audience is wanting. The speaker is then the prompter, and the listener stands openly before God. The listener, if I may say so, is the actor, who in all truth acts before God.

"Purity of Heart Is to Will One Thing" by Sören Kierkegaard

As Kierkegaard points out, it is so easy to consider the congregation the "audience" and the worship leaders the "actors" on the "stage" at the front of the church where God as the "director" causes us to perform at His prompting. On the contrary, it is God who is the audience observing the congregation on the stage of eternity. The congregation are the actors that have come before the altar of God for their act of worship. It is our responsibility as worship leaders, directing the order of worship, to prompt our congregation in the corporate worship of God.

Looking at our role in this way, we see that the responsibility we are called to is not a trivial one. Our role, along with the pastor, is to direct the eyes, hearts and minds of the congregation to the cross of Christ and help prompt their truthful and spirit-filled worship in church to its ultimate completion in service to the world's needs.

What do we sing?

In a world where we have a legacy of historical church music, an abundance of modern music and a sometimes bewildering variety of styles, what we sing to God during worship remains a very important question for the church. Here is the observation of a man who directed Anglican choirs during the first half of the 20th century.

Most people are indifferent to the words they sing in church. Even those who are critical of the verse they read throw all literary standards to the winds where hymns are concerned. Yet, as the church in its liturgy so carefully preserves the beautiful and dignified phraseology of the Bible and the early Prayer Book, as the preacher is expected to express his thoughts lucidly, logically and in the language of a scholar, surely it is not too much to ask that our hymns possess some literary merit. ... For no music, however worthy, can compensate for poor words.

The Organist and the Choirmaster, Charles L. Etherington, 1952

What he says about hymns could be said about anything we sing to God. We are to bring our first fruits as an offering to God, so when selecting music we should only bring the best we have.

We should select music with lyrics that helps support the message the pastor has been called by God to preach. Sometimes a message sung can reach into the heart where the same spoken words will fail. God made us musical people and knows that when we sing or listen to singing in worship we become open to His message. We need to understand this and plan services that do as much as possible to inspire both mind and heart in our songs.

Our Hymnal

The red hymnal called "The Hymnbook" that we use at St. Stephen Presbyterian Church was compiled in 1952 by our denomination, the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A). It was superseded by an updated hymnal in 1990, but the newer hymnal changed many things that do not appeal to our congregation. For example, it dropped the sung "Amen" that followed each hymn, changed the words of many traditional hymns to conform to some misguided policy of political correctness and included phonetically spelled foreign language verses of the most popular hymns. Nothing helps us focus on the worship of God like a couple of hundred English-speaking Christians stumbling through a verse of "Amazing Grace" in the language of the Cherokee...

Our hymnal represents a legacy of music that the saints who came before us have used to inspire and communicate the Word of God. We can find the words of Clement of Alexandria from the early 2nd century through lyrics composed shortly before its publication in 1952. Even the previously mentioned ancient Greek hymn "Phos Hilaron" is still in our hymnal as hymn number 61, "O Gladsome Light."

O Gladsome light, O grace of God the Father's face, The eternal splendor wearing; Celestial, holy blest, Our Saviour Jesus Christ, Joyful in Thine appearing. New, ere day fadeth quite, We see the evening light, Our wonted hymn outpouring; Father of might unknown, Thee, His incarnate Son, And Holy Spirit adoring. To Thee of right belongs all praise of holy songs, O Son of God, Lifegiver; Thee, therefore, O Most High, The world doth glorify, And shall exhault forever.

"Phos Hilaron" translated by Robert Bridges, 1899

Our hymnal is more than just a book of songs. It contains aids to worship, including common confessions, creeds and statements of faith. It also contains scripture readings, some intended to be spoken in unison and some divided to be spoken antiphonally between a leader and the congregation. It contains 600 different hymns, sung prayers and choral responses, which are cross-indexed seven different ways to make it convenient to find a particular hymn.

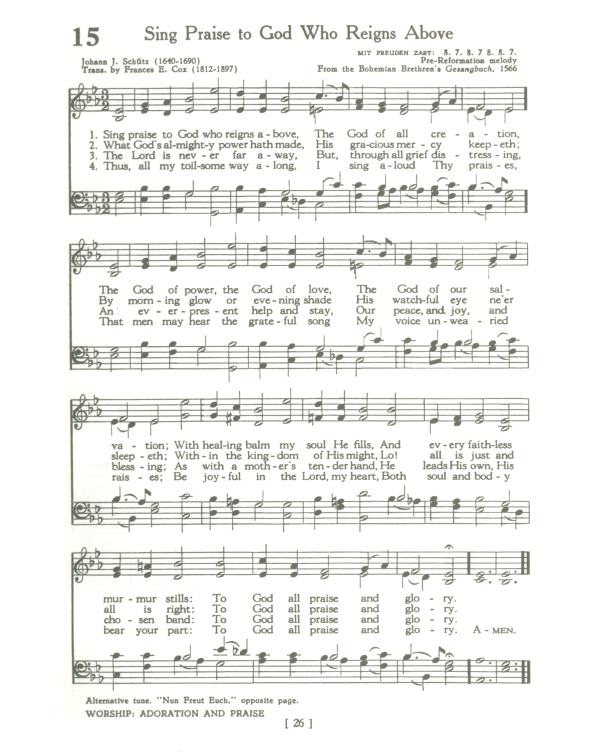

A typical hymn in the hymnal contains an amazing amount of information that may not be immediately obvious to the casual singer. In fact, most printed music has a number of common conventions to aid comprehension. Here are some common rules that should apply to most printed music.

- The title is usually in a larger font centered at the top of the first page of music.

- The author is generally located just under and to the left of the title.

- If the words are translated, the translator is usually listed just under the author.

- The composer is generally located just under and the to right of the title.

- If the music has been arranged or harmonized from an original composer, the person who arranged the music is listed under the composer.

- Any copyright information is generally found at the bottom of the first page of music.

A hymn in our hymn book has other attributes that are unique to its form.

- Hymns are named for their lyrics, usually the first few words or line.

- Hymn tunes also have names separate from the lyrics they may be commonly associated with. This name is generally located on the right just above the composers name.

- The verses of a hymn are usually strongly metered, meaning it has a certain number of syllables per line. The meter is usually listed to the right of the tune's name. Common Meter (or C.M.) is 8. 6. 8. 6. Long Meter (of L.M.) is 8. 8. 8. 8. Appending a D on the end of the designation means the meter should be doubled.

- Tunes are usually indexed based on the theme or topic. The topical index name is usually noted at the bottom of the hymn on the left side.

- Sometimes a hymn lyric is popular with more than one hymn tune. An alternate tune is usually specified above the topical index name.

A hymn tune's meter is very useful for replacing a less familiar tune for a given set of words. It also means that an author can write hymn text and fit it to an existing tune without having to be a musical composer.

In our example below of hymn 15 "Sing Praise to God Who Reigns Above", the meter is described as "8. 7. 8. 7. 8. 8. 7." which can be seen like this:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Sing praise to God who reigns a - bove, 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The God of all cre - a - tion. 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 The God of power, the God of love 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The God of our sal - va - tion; 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 With heal - ing balm my soul He fills, 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 And ev - ery faith - less mur - mur stills: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 To God all praise and glo - ry.

Even though hymn 16 "We Come Unto Our Father's God" has completely different notes and tune, since it has the same meter we can sing the words from hymn 15 without any problems.

Hymn 15 - Sing Praise to God Who Reigns Above

Identify the components of this hymn.